Reading Time: 9 minutes

Reading Time: 9 minutes☰ Navigate this post:

Why is alternative image content so difficult? It is! If it was not, then we would not need to keep writing about it. In this article I analyse and update W3C’s WAI Alt Decision Tree for everyday human consumption.

Note. This Post is extracted from my MSc dissertation in which I discuss improving our user experience (UX) of complex image editorial intent using complex cartoon and infographic content as models.

For help with designing alternative image content, read my article Writing for UX Optimizing Images Step 2: Alternative Content.

In a following Post, I engineer a more inclusive solution applicable to the most complex of images while minimising the effect on minimalist art direction.

Why must images be inclusive?

People with low vision also benefit from images (W3C WAI, 2019a).

When well designed or chosen, images are relevant and engaging. Their language is visual and can respond to problems, needs, and contexts (Dabner, Stewart, & Zempol, 2014, p.8). Images:

- Orient people to content and make it more pleasant and easier to understand.

- Can enhance learning, convey concepts, and offer memory cues (Abdelhamid, 1999; Clark, 2003; and Jewitt, Kress, Jogborn, and Tsatsarelis, 2001) and especially when sequenced (Cohn 2003).

Cartoon and infographic images can create significant barriers—and not just for people with visual impairments. Their accessibility (a11y) solutions apply to all types of image content.

The power of cartoons!

The political cartoonist, Patrick Chappatte (2010) notes the power of cartoons reaches every corner of the Internet. They can be used as weapons, to educate, divide, and coalesce: express or restrain freedom of speech and thought and influence hatred and tolerance. They are vehicles of healing, empathy, and understanding and conversely, Chappatte lists regimes that used cartoons to suppress and dehumanise, and for advantageous propaganda.

Cartoons and infographics

Cartoons differ to infographics only in their fictional versus reference situations (Pedrazzini & Scheuer, 2019) and share characteristics with illustrations, photographs, and diagrams. Their semiotic comprises the signifier and signified (Philpot Education, 2020a), which is not automatically conveyed to users accessing only text copy.

The problem

Screen reader users and people with different reading and learning strategies are unable to access cartoon, infographic, or other complex image content.

Dabner et al. (2014, p.178) instruct Web designers not to put important text inside images. Search engines cannot read it. The problem is that cartoons, cartoon strips, and infographics contain text. And when they don’t, they comprise an editorial intent that needs spelled out for some people.

What does the W3C say?

World Wide Web Consortium Web Accessibility Initiative (W3C WAI, 2019c) tutorials characterise seven types of images and guide the choice of accessible strategies by their purpose. (At Table 1).

| Image Purpose | Description and accessibility overview |

|---|---|

| Informative images | Images that graphically represent concepts and information, typically pictures, photos, and illustrations. The text alternative should be at least a short description conveying the essential information presented by the image. |

| Decorative images | Provide an empty text alternative (alt="") when the only purpose of an image is to add visual decoration to the page, rather than to convey information that is important to understanding the page. |

| Functional images | The text alternative of an image used as a link or as a button should describe the functionality of the link or button rather than the visual image. Examples of such images are a printer icon to represent the print function or a button to submit a form. |

| Images of text | Readable text is sometimes presented within an image. If the image is not a logo, avoid text in images. However, if images of text are used, the text alternative should contain the same words as in the image. |

| Complex images | Complex image such as graphs and diagrams convey data or detailed information, provide a full-text equivalent of the data or information provided in the image as the text alternative. |

| Groups of images | If multiple images convey a single piece of information, the text alternative for one image should convey the information for the entire group. |

| Image maps | The text alternative for an image that contains multiple clickable areas should provide an overall context for the set of links. Also, each individually clickable area should have alternative text that describes the purpose or destination of the link. |

The rotten Alt Decision Tree

We are advised by W3C WAI’s (2019d) to follow their Alt Decision Tree to help guide us on when and what alternative text to write for images. When followed and found compliant by automated testing tools, the UX of the images’ content relies on the quality of design.

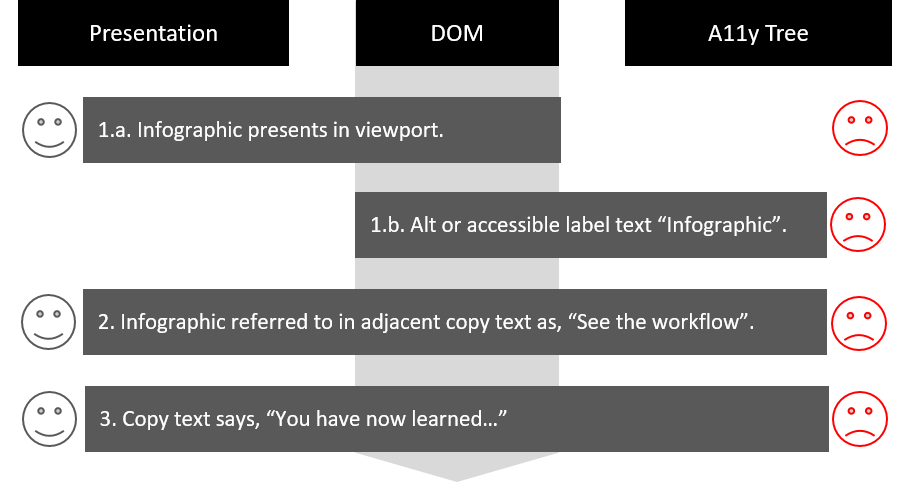

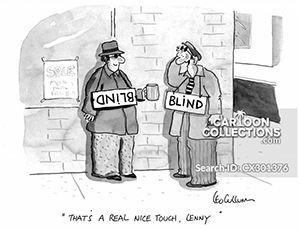

In Figure 1, the alternative text attribute describes what the image is. It is technically accessible and fails to describe the editorial intent of the image.

- An infographic image is presented.

- It displays in the viewport.

- It has an accessible label or alternative value of, “Infographic”.

- Visual visitors can each perceive the image text content and contexts. Screen reader users have not.

The author assumes visitors to have experienced the content, which increases the frustration of screen reader users.

What does the strategy at Figure 1 look and sound like? Figure 2 aims to explain:

Both the alternative text attribute and visible ‘caption’ fail to describe the situation, characters, props, or underlying satire. The captions have no programmatic association with the images. The headings are also unhelpful. For example, “Blind People cartoon 1 of 10”.

Note. Sydik (2007, p.161) applies the label, ‘redundant’ to images when their alternative attributes are unlikely to serve a purpose other than decoration and the WAVE tool detects. Although an attribute is available, it cannot serve a purpose when it is identical for two different images. The cartoonist, Maddocks (1986) describes: “The caption is something not to be ignored… unless of course the drawing says it all.” When a caption is important to an able person’s understanding of an image, then it is also important to people unable to access the image content.

Alternative text and alternative content are not a boolean accessibility choice. They work together and offer alternative content consumption channels to match an individual’s preferences and overcome limitations of technology (Godfrey, 2020).

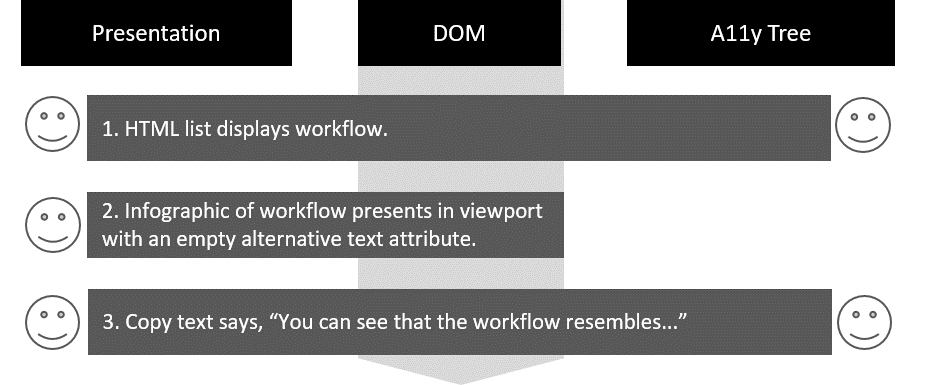

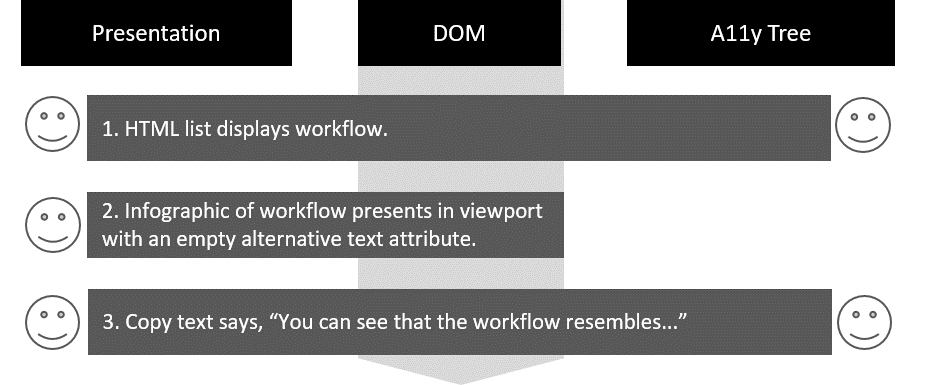

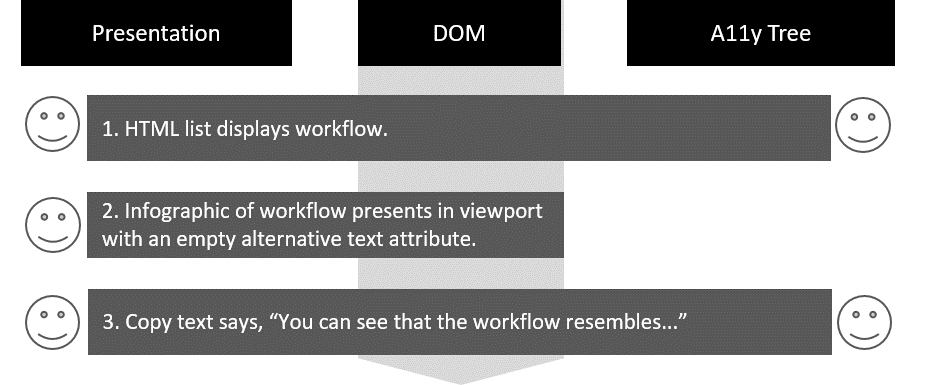

The UX design strategy is improved in Figure 3, when the editorial content is made accessible to the Accessibility Tree.

- HTML body copy text elements to describe the content. In this case, a workflow diagram.

- The image has no an accessible label and an empty alt value.

Visual visitors perceive the content according to their visual ability or cognitive preference. Screen reader users have access to the text-only content.

Pruning the Alt Decision Tree

Sydik (p.161.) places the responsibility for the specification and quality of alternative content on the author. The characteristics listed in Table 1, may be too technical to guide them. This may explain why alternative attribute practice can be poor?

I took the responsibility to refine (prune) them as detailed in Table 2.

WCAG 2.1. does not specify a maximum number of characters in an alternative text attribute. They recommend only that they are “short”.

| Image Purpose | Description and accessibility overview |

|---|---|

| Image text | When containing text:

|

| Informative | When informing a story or scenario content follow the guidance for Image Text. |

| Complex | When communicating content with complex graphics, story lines, and dialogue follow the guidance for Image Text. |

| Grouped | When images are presented in sequence:

|

| Functional | When used as a function trigger or link.

|

| Image map | When made interactive with two or more clickable areas:

|

|

Footnote: No maximum value is specified in WCAG 2.1.: only “short”. |

|

Note on the figure 100

Some automated tests report errors when alternative text values exceed 100 or 120 characters. We are told this string length exceeds the capacity of screen reader text windows and degrades Search Engine Optimisation (SEO). It seems the figure 100 is a legacy from W3C’s Draft test suite for WCAG 2.0. (W3C WAI, 2005) and the screen reader window issue results from that?

My opinion is that alternative texts can be any length with caution their display when images fail to load and concealing the content from visual users who may benefit it?

Shaking the ‘Tree

Now refined in Table 2, the editorial intent of an image may have more than one purpose including:

- Complex content

- Concepts and information

- Decoration

- Functionality

- Illustration

- Readable text

The lists at Tables 1 and 2 characterise the function within the HTML or presentation and not discrete image content features or intent. Non-technical authors and designers may not respond to that?

Removing the following programmable characteristics may help:

- Image maps

- Functional images

- Groups of images (a programmatic hierarchy)

The remaining features are then distilled into three groups (at Table 3).

| FeaturesTypes | Readable text | Complex content | Concepts and Information | Illustration | Functionality | Decoration |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Informative | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Decorative | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes |

| Text | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Complex | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

My Alt Decision Shrub

From Table 3 we can understand an image:

- Decorates and, or

- Illustrates and, or

- Informs (with text or complexity).

The new list (at Table 4) easily guides accessible strategies from the W3C WAI (2019d) Alt Decision Tree depending on overall editorial intent.

| Image Purpose or Intent | Description and accessibility overview |

|---|---|

| Decorate | Decorative or redundant images (Sydik 2007, p.161) are not necessary to understanding the document content. When the image is removed, nothing is removed from the content’s meaning or context.

Accessibility:

|

| Illustrate | Illustrative images support the document content. When we remove the image, we may remove content and, or the context needed for some users to understand the content.

Accessibility:

|

| Inform | Informative images have imagery, text copy, or data that may be essential to understanding, or are a part of the document content.

Accessibility:

|

|

Footnotes:

|

|

The Story Continues

Alternative Text attributes are not the end of this journey or story. We know that some alternative copy texts are only too long to fit comfortably within the attribute, or need expanding for some visual users to comprehend in their own style or preference.

The next stage is to engineer a more inclusive solution. And that is another Post entirely.

Reference this post

Godfrey, P. (Year, Month Day). Title. Retrieved , from,

References

Note. To avoid (my) confusion, references appear in the order presented in the dissertation.

- Abdelhamid, T. (1999). The Multidimensional Learning Model: A Novel Cognitive Psychology-Based Model for Computer Assisted Instruction in Order to Improve Learning in Medical Students. Medical Education Online 4. Doi: 10.3402/meo.v4i.4302

- Cartoon Collections. (n.d.). Blind Cartoons [Commercial Enterprise Site]. Retrieved from https://www.cartooncollections.com/directory/keyword/blind

- Chappatte, P. (2010, July). The Power of Cartoons [Video File]. Retrieved from https://www.ted.com/talks/patrick_chappatte_the_power_of_cartoons?language=en

- Cohn, N. (2003). Early writings on visual language. Carlsbad, CA: Emaki

- Clark, R. (2003, August 11). More than just eye candy: graphics for learning. Retrieved from http://ww.clarktraining.com/content/articles/MoreThanEyeCandy_part1.pdf

- Dabner, D., Stewart, S., & Zempol, E. (2014). Graphic Design School. London, UK: Thames & Hudson.

- Godfrey, P. (2020, February 1).Writing for UX, Optimizing Images Step 2: Alternative Content [Web Article]. https://www.learningtoo.eu/articles/writing-for-ux-optimizing-images-step-2.htm

- Jewitt, C., Kress, G., Ogborn, J., & Tsatsarelis, C. (2001). Exploring Learning Through Visual, Actional and Linguistic Communication: The Multimodal Environment of a Science Classroom. Educational Review, 53(1), 5-18. doi: doi.org/10.1080/00131910123753

- Maddocks, P. (1986). How to be a cartoonist. London, UK: Elm Tree Books.

- Pedrazzini, A. & Scheuer, N. (2019). Modal functioning of rhetorical resources in selected multimodal cartoons [Abstract]. Semiotica. Doi:10.1515/sem-2017-0116

- Philpot Education (2020a). 2.1. Analysing Visual Texts, 2.1.1 Deconstructing image [Academic Module]. Retrieved from https://www.philpoteducation.com/mod/book/view.php?id=222&chapterid=143#/

- Sydik, J. (2007). Design Accessible Websites. Raleigh, NC, USA: Pragmatic Bookshelf.

- W3C WAI (2005, August 11). HTML Test Suite for WCAG 2.0 Test 3 – Image Alt text is short. Retrieved from https://www.w3.org/WAI/GL/WCAG20/tests/test3.html

- W3C WAI. (2019a, November 11). Authorized Translation of WCAG 2.1. In Danish [Web Log Post]. Retrieved from https://www.w3.org/blog/news/archives/8190

- W3C WAI. (2019c). Image Concepts. Retrieved from https://www.w3.org/WAI/tutorials/images/

- W3C WAI. (2019d). An alt Decision Tree. Retrieved from https://www.w3.org/WAI/tutorials/images/decision-tree/

Images

- Bates, W. (1920). The cure of imperfect sight by treatment without glasses [Electronic File, p.211, updated by the author]. New York, NY: Central Fixation Publishing. Retrieved from https://archive.org/stream/cureofimperfects00bate/cureofimperfects00bate#page/n7/mode/1up

1 thought on “Shaking the Alt Decision Tree”